Making the List: Understanding How You Came to be Educated

(Here is another compelling post from Fairhaven School parent and writer Johnna Schmidt. Enjoy!)

In a bid to try to understand how my sons may come to be educated, I’ve been trying to understand how I myself have experienced education. Always a list-maker, I’ve devised the following exercise and have found it clarifying:

Draw a line down the center of a piece of paper. On one side list 4 or 5 of the most significant life-learning, non-academic experiences you’ve had. Don’t worry if you’re not sure you’re getting the very most impactful ones. You can do this again next year and you’ll have a slightly different list. Just think of things that have changed your life, have molded you into who you are. These may be special projects or unexpected hardships, life challenges or opportunities, etc, any context in which that you feel you really learned a great deal.

On the other side, make a list of the 4 or 5 most significant teachers in your life, or academic courses that you’ve taken that have been the most important. Restrict this side to academic-context only learning. Place an asterisk next to the teacher’s name if you consider that person a mentor instead of merely a teacher, that is, you had a one-on-one relationship with that teacher, or some kind of emotional connection, or received advice from them that was especially important.

Take a moment to reflect upon your education as a whole. Looking at your list, what stands out to you? What or who has been the most important?

I have done some version of this exercise with over 20 people at this point. What stood out to me immediately was the distinction between “mentoring” and “teaching.” Very little impactful learning actually seems to occur in traditional classrooms. Most people have had special relationships with adults in their lives who helped guide them in some way at some critical juncture, or have learned from projects they themselves took on, and/or gained important life skills from situations that developed quite outside of anyone’s control. One young woman who is a wonderful writer said the most important thing was that she had teachers who suggested things she would like to read. And elderly man talks about how his shop teacher let the students make whatever they wanted, and just helped them along on their own projects. This kind of individualized and thoughtful guidance is exactly what students at Sudbury model schools such as Fairhaven School can expect. What a contrast from the current mode of classroom instruction, where reading lists are short and standardized to make room for the tests that all publicly funded schools are mandated to administer.

But the other thing that is immediately apparent from doing this exercise, is that learning is happening all the time, and often some of the deepest and most potent forms of education occur outside of academic environments. We learn when a parent dies, or a friend betrays us. We learn when we take a stand on an issue, or when we pursue a goal even though those around us think it is silly or not worthy in some way. Fairhaven students talk. When Osama bin Laden was killed, they talked about it. When the shooting happened in Connecticut, they talked about it. When any one of them is suspended from school, there is a lot of talk. In this way, they continue to develop nuanced and confident thinking about complicated issues. What some might call “critical thinking” and what I call “money in the bank” because these kids are going to interview extremely well. Social skills and creative thinking are the new currency, in my book, and an awful lot of the factual memorization and multiple choice type thinking conventional schools favor is insanely outmoded.

Perhaps you’re wondering when and how they learn how to read and write. Believe it or not, they all do in various ways, and those skills simply don’t take as long to develop as you might think, when you have a motivated learner. John Taylor Gatto, a New York State Teacher-of-the-Year award winner who wrote “Dumbing Us Down,” writes that the entire K-6 standardized curriculum could be taught in a total of 100 hours if the student actually wanted to learn it. He goes on to state that what you have when you remove free will from an educational setting is mere “schooling” and not the kind of thinking any parent would really like their child to be developing in preparation for the adult world, though it may make them a more compliant child in institutional settings.

Recently my nine-year-old son participated in a therapeutic mode of assessment called “Floortime” where he was observed while in a pedagogical but playful setting. This was because he often wants to do things other than what is being taught in his classroom. He wanders off, fidgets, can’t seem to just sit there and listen like he’s supposed to. We were told after the Floortime assessment that the reason our son fidgets so much and can’t seem to focus on the task at hand at school is because he is not stimulated enough. He needs more than to be sitting in a circle looking at a book, or sitting at a table given instructions on what to do with a piece of paper and a pencil. In short, he has been bored at school.

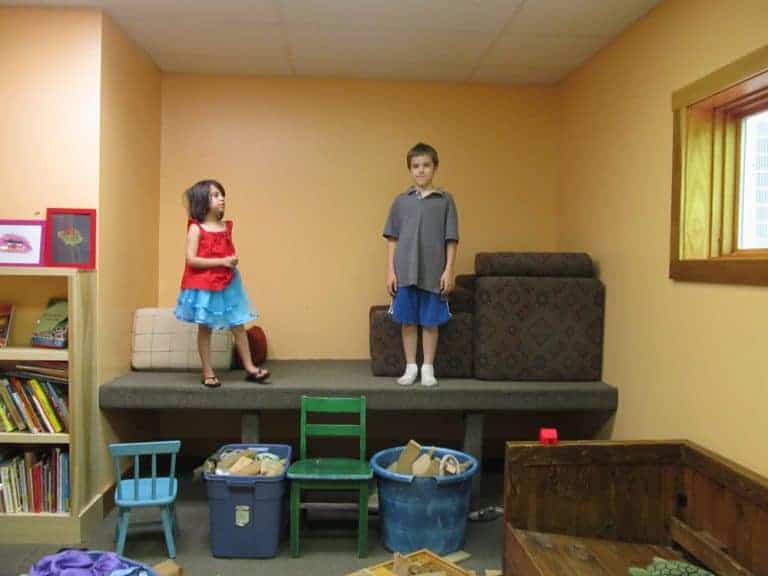

I found this so interesting because my son is never bored at home, where to be honest he is pretty much left alone with very little structured activity, and very peripatetic in his interests. He may be found asking me for metal springs, tape, cardboard, and string, or on the swing, or taking apart an old record player, or arguing with his brother, or playing a game on his kindle, or pouring himself too much cereal, or dancing from room to room, or watching multiple episodes of some inane TV show, or taking something out of the recycling bucket and banging on it until it breaks, or hugging the dog, but in any case he is never bored. He has been going to more conventional schools than Fairhaven for the past two years but he has never stopped requesting a return to “Fairheaven” as he calls it, and thank goodness, this year we are finally able to send him back.

I don’t know what his list will be, of most important educational experiences. I’m pretty sure, if we had left him in conventional schools and someone had forced him this coming year to sit still, follow directions, and read and write at a higher level, that would not appear on his list later in life, and it would count not as “education,” but as mere schooling, possibly at great cost to his self-esteem. I am so happy to be avoiding that risk. Free the children, I say, they know what they want to learn, and they will find their way.

by Johnna Schmidt

July, 2013