The School That Saved My Son

My son is funny and witty and full of life- and information. At not quite sixteen, he has started pondering what he wants to do with his life. But things weren’t always this good. Three years ago, Simon was almost immobilized by migraines, crushed by depression, harassed by the public school system for absenteeism and totally bored by the school when he could attend. He was threatening suicide. Nothing could be further from the marvelous baby and little kid Simon had been.

In 1993 my husband and I adopted a beautiful baby boy we named Simon. From the beginning, he was special. Born six weeks premature, he was healthy but sometimes forgot to breathe. He spent his first five weeks in a neonatal intensive care unit on a cardiac care monitor entertaining the nurses. By graduation from the NICU, he could pull his leads off to make the monitor alarm and nurses come running. He would be holding the lead wires laughing. The nurses, struggling with many really sick babies, loved his antics and said he was one of the special kids, aware of the world from day one.

We brought him home and that sunny personality and driving curiosity continued to flourish. While he met all of his physical milestones on times, he was way ahead in the cognitive areas. We talked to him, read to him, and showed him the world, and he soaked it up. By eight months he was talking. At eleven months he spoke his first sentence, “Momma, read book now.” He could carry on a conversation before he started to walk at thirteen months. At eighteen months the pediatrician asked me if he had any words and I said; I had stopped counting at one hundred and fifty. He was fully conversant and understandable to anybody. By two he had learned the alphabet and his numbers and colors. If he heard a word he did not know he demanded a definition and from then on the word was his and was used appropriately. At some point he started to read, but we were not exactly sure when.

Simon and I would read a book, or see a bug, or watch a TV show that would lead us down a discovery path. Simon would want to read all the books on a topic. For example, at two-and-a-half he saw a Magic School Bus show on volcanoes. He had me read to him everything available on volcanoes in the library. He decided to be a volcanologist and to that end dictated and illustrated his own book on volcanoes. Between two and five he followed this path on a variety of topics- bugs, fish, rocks, dinosaurs, ancient Egypt, the ocean and others I can’t even remember.

Simon also loved music and could sing any song he ever heard. Once, while driving in the car, a Strauss waltz came on and Simon at two described it “like chocolate.” In listening to Beethoven’s Pastoral symphony he told me he saw the storm. Only recently did I discover that Simon still has that synesthesia and sees music.

Before he turned five, Simon and I lost his Dad suddenly. It was only then that I discovered that my husband, who was chronically ill, had been preparing Simon for this and “downloading memories” that would be triggered during Simon’s childhood. Months later when I took him fishing he told me stories about Daddy fishing as a little boy, and a year later told me stories about Daddy camping. All stories I could confirm with siblings. It was an amazing gift and the memories kept coming for many years.

Despite the wonderful memories, it was hard for Simon to lose his Dad. Fortunately we found a wonderful private kindergarten with before and after care where he thrived. By second grade, however, they were concerned about his handwriting, his fidgeting and periods of depression. His curiosity and intellectual drive were fading. An extensive cognitive and psychological evaluation indicated he was extremely bright, possibly had attention-deficit, and had some depression and poor fine-motor coordination. We all assumed the depression was a combination of the loss of his father and hereditary since his birth father suffered from depression. This is where our downward spiral began. We were referred to both an occupational therapist and a psychiatrist. The occupational therapist made him go backwards from cursive to printing and caused such turmoil that to this day he does neither. The child psychiatrist put him on an antidepressant not recommended for children. This led to a condition called abdominal migraines which lasted six months and led to significant absences.

By this time Simon was in third grade, and struggling with math (the only subject he was average in) and handwriting. An insensitive math teacher humiliated him and he shut down. Sadly, he equated poor handwriting with poor writing, and wrote virtually nothing for years. The words that had poured out were gone. This was the year jet liners crashed into the World Trade Center and life changed for everyone. So much loss. My sensitive child had lost his father, and now he felt no one was safe. School was a place to go when Mom went to work. He was learning nothing. The books being read in school were books Simon had devoured at four but he was not allowed to move ahead. Subjects were covered at third grade level and Simon was not encouraged to go beyond. When he was bored, he fidgeted and stared out the window longing for escape. They punished him. When I suggested that he be allowed to read beyond when he finished his work they said no. We knew we needed to find another school.

After searching we gave our neighborhood public school a try. The principal, with a PhD in Latin, was the kind of person who could appreciate Simon. He matched teachers and children with uncanny perception. Simon was immediately given an electronic keyboard to move beyond the handwriting issue and his fourth grade teacher spent a year trying to make him more comfortable with numbers. Testing at this time indicated that he had the broad knowledge of a 39-year-old. There was no gifted program, but there were gifted teachers who helped him grow. But still there was no intellectual challenge and his frustration and anger grew. The set county curriculum and pressure of “No Child Left Behind” left little leeway for this child. Simon pointed out that going to school was getting in the way of learning, and he didn’t like that. The migraines (this time in headache form) came back as did the depression. A week of psychiatric day treatment helped. He returned to a nurturing environment and started to blossom socially. His sixth grade teacher was a quiet and intellectual young man who finally inspired Simon to start creative writing again, something that had been suffocated by the handwriting issue. A novel and wonderful poems poured forth. Middle school was the next step and we were assured that they had a talented and gifted program which would inspire Simon.

In middle school however, Simon went from a warm and supportive place to a prison camp. No breaks, no water, no talking, no respect for children and very little learning. No understanding of his challenges despite an IEP and accommodation. On back to school night the principal told us our children were troublemakers and had to be controlled and restricted and she kept her work. My sensitive boy, again suffering from migraines, was not allowed to get a drink of water between classes or carry a water bottle. The nurse would not allow him to stay in her office when he had a headache and the teachers would not allow him to put his head down or close his eyes. When he stayed home we were both harassed over absenteeism and threatened with dire consequences. The vice principal told him him this was the best time of his life. He threatened suicide. Teachers, on some sort of work slowdown, refused to post homework on the site available for that or provide it to parents. They then punished Sim0n for not turning it in. The touted “Talented and Gifted Program” he was in simply meant they put him in Algebra, a class he was not ready for. There were no challenges in other areas. He came home once in total disgust and said, ” Mom, they covered the Renaissance in two days, what is wrong with these people?” By April I pulled him out of the school, unsure what to do or where to go.

Then I remembered that when Simon was younger, his pediatrician had mentioned Fairhaven, a new Sudbury School which was a wonderful place for another gifted patient of his. I looked at it, but at the time this place with no curriculum or classrooms seemed extreme. When and how did the kids learn? My husband, a PhD in psychology, had been a product of the Catholic school system, while I had done well in public schools and earned an MA myself. I passed on a such a far-out place. Now I was desperate. My concern was no longer ab0ut a good college for Simon, but survival.

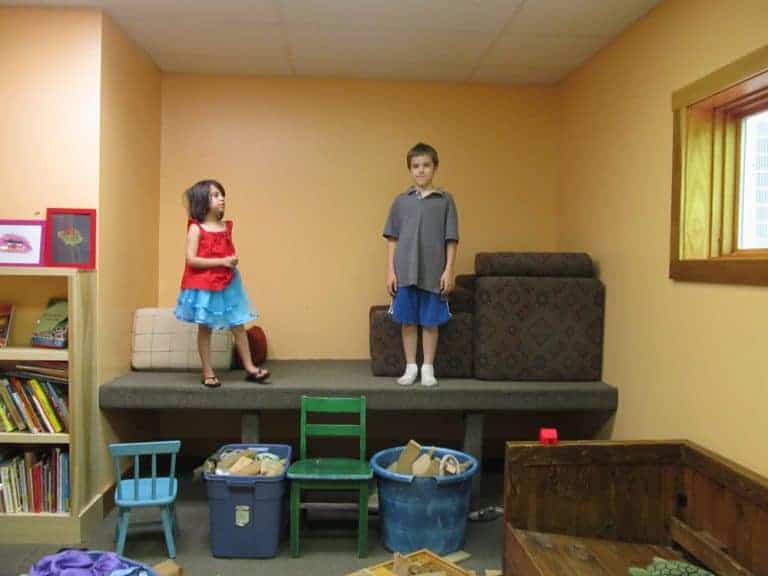

A visiting week at Fairhaven cinched the deal for both Simon and me. My earlier concerns about his academic needs dimmed when i viewed his unhappiness. My goal was getting a happy, healthy kid back. He came back, bit by bit, over the last three years. The abandoned kittens found the first day of school seemed an omen. We brought one home and she joined our dog and other two cats and helped our family heal. The first year he mostly sat around or slept when in the grip of migraines. His companions at school that year seemed to be the younger girls. He could read to them and tell them stories and they let him retreat to a more comfortable social situation. It was at that time he also found a mentor among the older students. Anne was a wonderful young woman who had fought depression and school issues herself, and supported Simon in his healing. He also found male staff members who were interested in ideas and words and not just sports. The migraines were still around, but they were accepted as part of Simon.

By the second year Simon was relaxing and becoming more integrated into school life. Another mentor, Paris, had been at Fairhaven since the beginning, and educated Simon in the inner working s of a democratic school. She also reawakened his intellectual interests and introduced him to the joys of the theatre and music. He would come home bursting with ideas and arguments about politics, religion, economics and the world order. He became an expert on the Broadway musical, malaria, sharks and rays, and European history.

Unfortunately the migraines didn’t go away, and the depression they brought on deepened. His psychiatrist felt that hormones where causing the increasing intensity and length of the migraines. He also felt that emotionally Simon was approaching a crisis not uncommon in children who lose a parent so early in life. He was going to have to come to terms with becoming a man without his father. The crisis might be rough and it was. Simon spent a week in a residential treatment facility and returned a happier person. He was flooded with cards and love from students when he was hospitalized, and welcomed back with open arms. His migraines reduced and he threw himself into school life. He would come home that spring covered with mud and dirt from exploring the school’s stream hunting for fossils. He even completed a weekend school-sponsored camping trip on the beach.

Over the summer Simon attended Fairhaven Camp with his best friend, and grew six inches. The migraines retreated, then returned. Simon may live the rest of his life with migraines, but at Fairhaven he is learning that he can live with them and learn and grow. He is funny and witty and full of life as well as information. He turns sixteen soon and has started pondering what he wants to do with is life. He tells me he will know when his is ready to leave Fairhaven. I have no doubt that he has the tools and the confidence to make decisions that are right for him. I don’t know whether I will agree with his choices or not, but I know that they are his to make. I also know that he now knows how to manage and prevent the depression that has followed him. The other day he said, ” Life is generally good,” to one of his fellow students. He then looked at me and said “and I never used to think that at all.” Fairhaven gave him that confidence and joy. I have my son back.

A Fairhaven School parent

March, 2009